In my previous article, I introduced the water cycle. This follow-up post is a discussion about watersheds. Conservation Ontario defines a watershed as:

“An area of land that catches rain and snow and drains or seeps into a marsh, stream, river, lake or groundwater”

In other words, within a watershed (sometimes referred to as a drainage basin or a catchment), all water inputs (precipitation) flow to the same place (which could be a stream, wetland, lake, ocean or other water body). Understanding watersheds helps us learn about our role in the water cycle. If we understand our watersheds, we can understand where our water comes from and where it goes. We can also learn how different activities (such as land development, water use, waste disposal, road salt, for example) might be impacting our watershed, and inevitably, our water resources.

As a continental-scale example of watersheds, the map below (from the Canadian Federal Government) shows the main watersheds of Canada. Water in the green area in the west flows to the Pacific Ocean. Water in the purple section in the northwest flows north to the Arctic Ocean. Water in the yellow section flows to Hudson’s Bay, and water in the light-blue/teal section flows to the Atlantic Ocean.

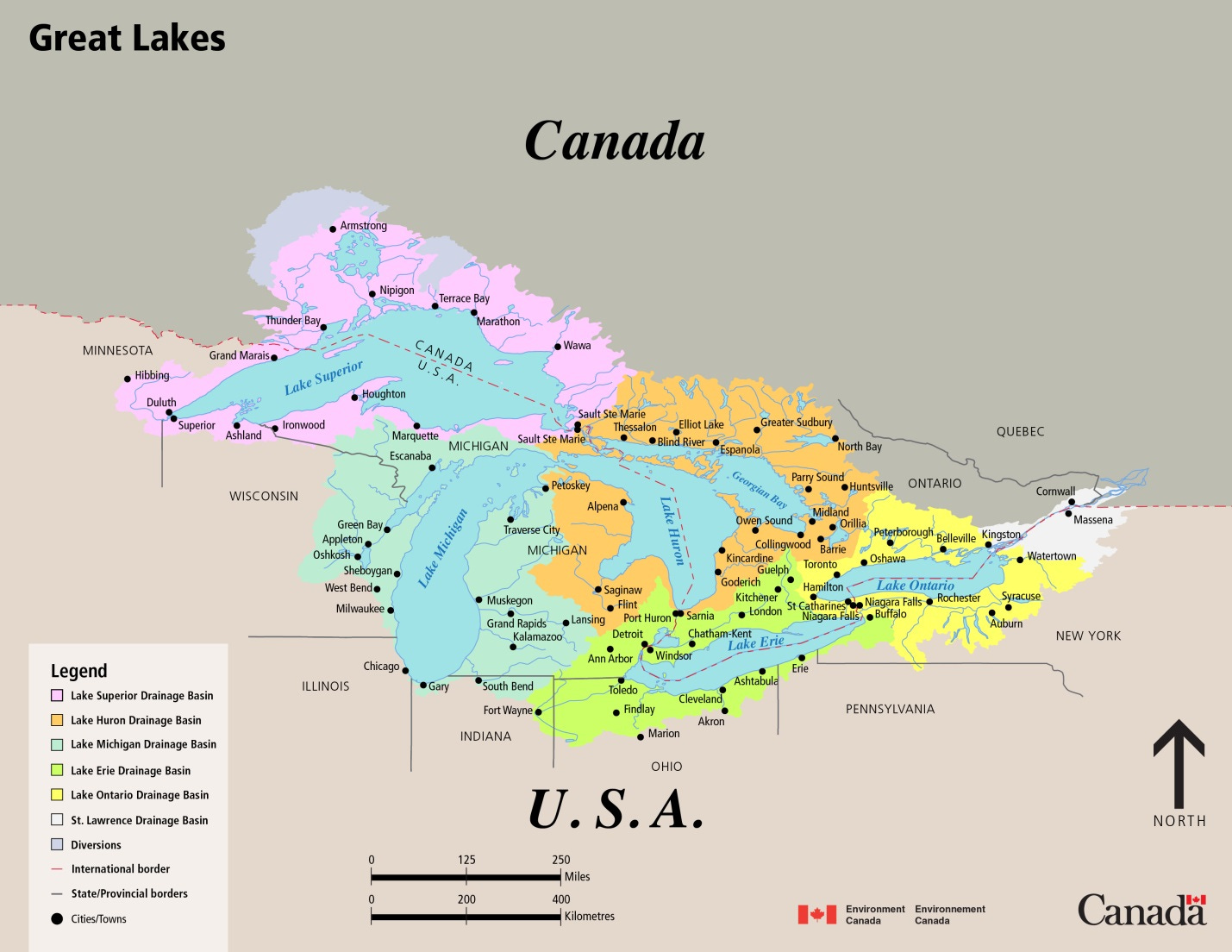

There are just four main watersheds for the entire country of Canada (five, if you count the small brown slice of land in southern Saskatchewan and Alberta, where water flows to the Mississippi River and eventually the Gulf of Mexico)! Simple enough, right? Well it can get more complex. Let’s look at the Great Lakes area in central Canada. In the map above, The Great Lakes lie within the watershed that drains into the Atlantic Ocean. Within the Atlantic watershed, the Great Lakes form a watershed of their own, where all water flows to one of the five Great Lakes. If we look at a close-up of the Great Lakes, we can divide the Great Lakes watershed into smaller watersheds - one for each Great Lake (smaller watersheds are often referred to as subwatersheds). The map below, from Environment Canada, shows each of the five different (sub) watersheds for the Great Lakes: Pink for Lake Superior, light teal-green for Lake Michigan, orange for Lake Huron, lime-green for Lake Erie and yellow for Lake Ontario. All of the water within these watersheds eventually makes its way to the St. Lawrence River, which flows into the Atlantic Ocean.

But let’s look even closer. The map below (from the Erb Family Foundation and the Nature Conservancy) shows the same five watersheds for each of the Great Lakes with further subdivision within each watershed.

If we zoom in on the Canadian side of Lake Ontario (see below), we can see more detail of these smaller watersheds within the Lake Ontario watershed. On the north shore of Lake Ontario, watersheds drain to the south from the Oak Ridges Moraine to Lake Ontario. The Trent watershed covers a large area that extends north towards Algonquin Park. All precipitation within the Trent watershed drains to the Trent River system, which flows to Lake Ontario.

The Trent watershed can be subdivided even further, as shown on the map below. Each subwatershed show below drains into a different tributary of the Trent River.

So if you live on the Burnt River, you’re in the Burnt River watershed, which lies in the Trent watershed, which lies in the Lake Ontario watershed, which lies in the Great Lakes watershed, which likes in the St. Lawrence River watershed, which lies in the the Atlantic Ocean watershed!

The Oak Ridges Moraine Groundwater Program (ORMGP) have developed mapping tools to divide these subwatersheds even further. In this map below, each small polygon shape is a subwatershed where all water flows to a section (or “reach”) of a stream.

One final point is that these watersheds are typically drawn using stream networks and a map of the elevation of the ground surface (these elevation maps are referred to as a digital elevation models, or DEMs). Water always flows downhill, so on land, water will always flow towards a body of water (stream, pond, lake, ocean…). I have neglected to mention groundwater in this article because watershed maps are drawn without consideration of groundwater. The flow of shallow groundwater (close to ground surface) typically follows the slope of the ground surface. However, deeper groundwater can flow across the watershed boundaries. And that’s a topic for another day!

Excellent article about watersheds and sub-watersheds delineation

I am learning so much-thanks, Steve! I am looking forward to learning about how deeper groundwater can flow across the watershed boundaries. So interesting! - McB