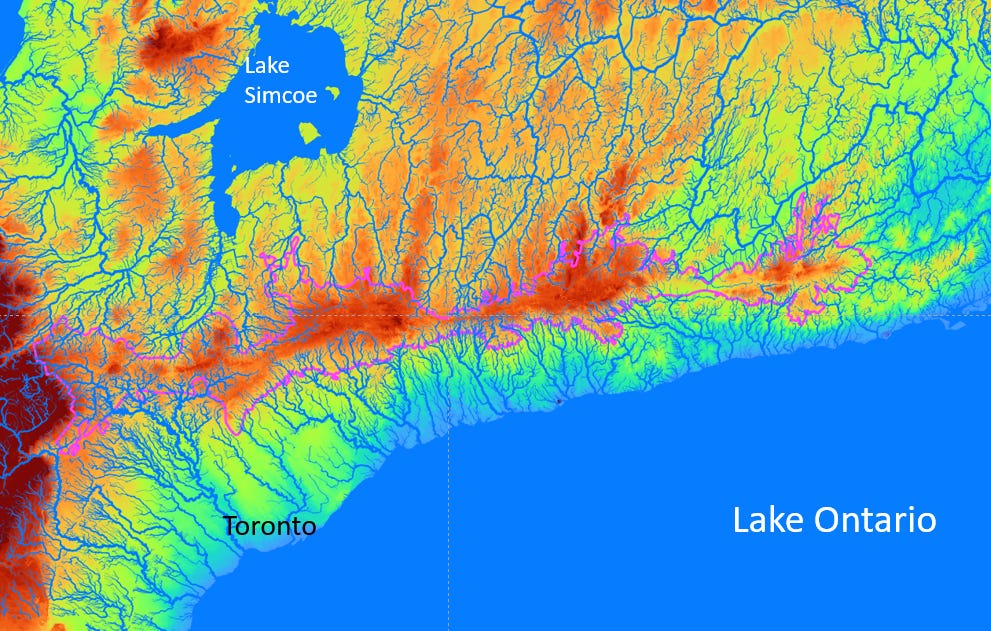

The Oak Ridges Moraine (I’ll refer to this as “the Moraine” for this article) is an important geologic feature that lies north of the city of Toronto. The Moraine is about 160 kilometres long and extends west-to-east from the Niagara Escarpment to the Trent River. In the map below, the planning boundary of the Moraine is outlined in pink. Lake Ontario is the south and Lake Simcoe is to the north.

The Moraine was deposited during the last ice age, over 13,000 years ago. Two separate lobes of the glacier that covered this area converged to form the Moraine. In the figure below (click here for reference), glacial lobes from the north (Georgian Bay lobe and Simcoe lobe) and from the south and east (Ontario lobe) resulted in the formation of the Moraine1. Due to the way in which the Moraine was deposited, it represents a topographical high, and this higher elevation results in some unique features of the Moraine.

As we know from the previous discussion on the water cycle, when rain falls on the ground, water flows downhill along the ground surface2. This water will eventually reach a stream or pond or lake. Therefore, the slope of the ground surface plays an important role.

The map below shows the Oak Ridges Moraine. The ground surface elevation is indicated by the colour ramp, with warmer reds representing higher elevations (the Niagara Escarpment can be seen as the dark red area in the west), and cooler blues representing lower elevations. The Moraine is at a higher elevation than the areas north towards Lake Simcoe and south towards Lake Ontario.

As a result of the higher elevation, streams flow from the Moraine south towards Lake Ontario and north to Lake Simcoe, Georgian Bay and the Trent River. This shows how important the Moraine is to the streams in this area.

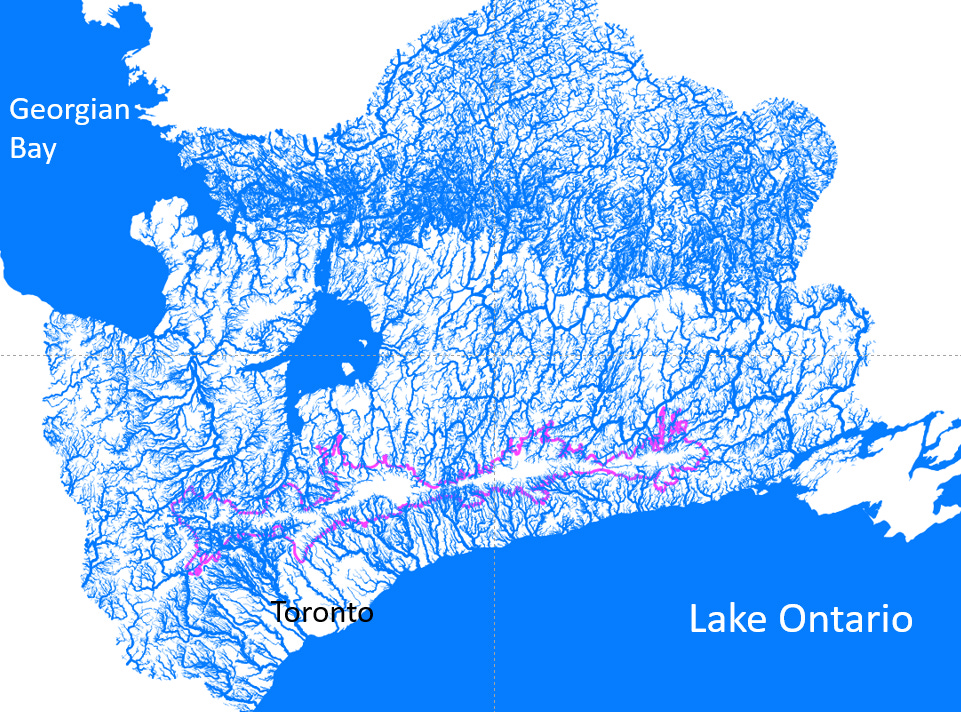

Let’s expand the map and look at the streams over a larger area. At this scale, there are so many streams, the map looks almost entirely blue!

That’s a lot of streams! Not all of these streams start at the Moraine, but let’s look at these streams and their watersheds in a little more detail.

The first area is in the northwest portion of our area of interest. I’ve coloured the streams red in the map below. If we start our focus on the Moraine in the south, we see that streams are flowing north of the Moraine. Some streams flow into Lake Simcoe while some (notably the Nottawasaga River, which flows south to north, east of Lake Simcoe) flow directly to Georgian Bay. Water in Lake Simcoe drains to the north and eventually also flows into Georgian Bay. The large blue arrows show approximate streamflow directions. I’ll refer to this group of watersheds as the Georgian Bay-Lake Simcoe watersheds.

Moving to the northeast, the watersheds look like this (streams are coloured purple):

This is the Trent River watershed. The Trent River, which is hard to distinguish at this scale, gets its water from the highlands to the north (where streams flow north to south) and from the Oak Ridges Moraine to the south (where streams flow south to north). The Trent River then flows to the east and south where it discharges into Lake Ontario at Trenton. As before, the large blue arrows indicate the approximate flow directions of streams in this watershed.

This next map shows watersheds and streamflow direction arrows for streams that flow south from the Oak Ridges Moraine to Lake Ontario.

Conceptually, the streamflow system is a little simpler here. I’ve separated the watersheds into different groups based on boundaries of Conservation Authorities. Starting in the west, the blue watershed is the Credit River watershed, followed by the orange area, which represents the watersheds of the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA). The Humber, Don and Rouge Rivers are the biggest rivers in the TRCA.

The yellow watersheds are part of the Central Lake Ontario Conservation Authority (CLOCA) and the green watersheds are in the Ganaraska Conservation Authority. At the easternmost tip of the Moraine, there are small watersheds shown in grey. These small watersheds are part of the Lower Trent Conservation Authority but do not flow to the Trent River. Instead, they flow directly into Lake Ontario.

Looking at all these watersheds, as seen below, scale of the area where streams are affected by the Oak Ridges Moraine is enormous. This map also shows the clear line where the Moraine represents a flow divide, separating rivers that flow north from those that flow south. And, quite frankly, I find these kinds of watershed maps very aesthetically pleasing.

This next map shows a close up of the coloured watersheds and the outline of the Oak Ridges Moraine planning boundary. This map more clearly shows the importance of Moraine and its role in the formation of the headwater streams that feed the larger rivers to the south3.

I’ll leave you with this image of the Humber River watershed. The Humber River is designated as a Canadian Heritage River System (CHRS) and is the only such river in this area.

Also, doesn’t the stream network look like a tree?

In conclusion, in light of the recent announcements from the Ontario government to develop more land, it is critical that any new development projects consider environmental impacts, including how these developed lands will affect our valuable water supplies.

Note: All maps (except for the second image) were drawn by the author using open-source software (QGIS) and publicly-available data.

The geologic term moraine refers to unconsolidated material (sand, silt, clay, gravel) that has been deposited by a glacier. There are different types of moraines. For example, lateral moraines are deposited along the sides of a glacier (parallel to the flow direction of the glacier. End moraines form at the end of a glacier. The Oak Ridges Moraine is a little more complex. The most-recent period of glaciation in this area was a little over 10,000 years ago; however, there were different periods of advance and retreat of the glacial ice earlier. This resulted in a complex deposition of glacial materials.

For this article, I’m focussing on what happens to water at the ground surface. When rain hits the ground, some of it will seep into the ground and become groundwater. Some rain water is also consumed by plants, and some water evaporates into the atmosphere.

Since this article focusses on streamflow, I have not mentioned the importance of the Moraine as a groundwater recharge area. This will be the focus of another article.

Fantastic article! As CEO of the Oak Ridges Moraine Land Trust, I often am asked to explain why the Moraine is so important our region. These colourful maps are a truly wonderful way to show how the water flows. Can I have your permission to use these maps in future presentations?

ok